General Introduction to the Marsden Magazines

By Robert Scholes

General Introduction to the Marsden Magazines

Are The Freewoman (1911-1912), The New Freewoman (1913), and The Egoist (1914-1919) one magazine with three names, or three magazines with one editor? Actually, they are all of those, and more—and perhaps less, as well. Dora Marsden edited all three, but for a time she had a co-editor, Mary Gawthorpe, in the first magazine, while another co-editor, Harriet Shaw Weaver, would in time become chief editor of the third. The magazines also changed subtitles three times, though these name changes are mostly out of sync with the magazine’s other changes in title. Perhaps, then, the Marsden magazines are more than three in number, or perhaps they are a single chameleon that eludes final classification.

To help readers get a handle on the slippery identity of these magazines in the MJP digital editions, we are offering a general introduction to the whole set in addition to separate introductions to the individual titles.1 In this General Introduction, we shall mainly be concerned with the transitions, or the history of these journals, as different ideas came to dominate them—and different areas of modernity attracted the attention of the editors and their contributors—even as the contributors and staff changed as well. These changes, as it happens, did not align themselves neatly with the shifts in the journals’ titles and subtitles. The editors also shifted irregularly, with Assistant Editors sometimes being named in the masthead, and sometimes not. Rebecca West, for example, was an Assistant Editor for four months, but was never so named. And Ezra Pound assisted for a couple of months as well, without being named, and he continued to recommend things after his official connection ended. Dora Marsden herself had an editorial title for the entire run, but she was only a “Contributing Editor” for the last four and a half years of The Egoist, with Harriet Weaver acting as the Editor. Assistant editors came and went, while the frequency of publication changed from weekly to semi-monthly, to monthly, to irregular, and the price gradually increased from three pence to nine. An attempt has been made in the chart below to track all these changes, which are marked in red:

| date | title | subtitle | masthead info | other info |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nov 1911 – Feb 1912 | The Freewoman | A Weekly Feminist Review | Eds. Dora Marsden, Mary Gawthorpe | Weekly, 3 pence |

| Mar – May 1912 | The Freewoman | A Weekly Feminist Review | Ed. Marsden | Weekly, 3p |

| May – Oct 1912 | The Freewoman | A Weekly Humanist Review | Ed. Marsden | Weekly, 3p |

| Jun – Sep 1913 | The New Freewoman | An Individualist Review | Ed. Marsden | Semi-Monthly, 6p; Harriet Weaver, treas.; Rebecca West, Asst. Ed. (helped by Ezra Pound Aug-Sep) |

| Oct – Dec 1913 | The New Freewoman | An Individualist Review | Ed. Marsden | Semi-Monthly, 6p; Weaver, treas.; Richard Aldington, Lit. Ed. (not on masthead until Dec 15) |

| Jan – Jun 1914 | The Egoist | An Individualist Review | Ed. Marsden, Asst. Eds. R. Aldington, Leonard Compton-Rickett | Semi-Monthly, 6p; Weaver, treas. |

| Jul – Dec 1914 | The Egoist | An Individualist Review | Ed. Weaver, Asst. Ed. Aldington, Contrib. Ed. Marsden | Semi-Monthly, 6p |

| Jan 1915 – May 1916 | The Egoist | An Individualist Review | Ed. Weaver, Asst. Ed. Aldington, Con. Ed. Marsden | Monthly, 6p |

| Jun – Dec 1916 | The Egoist | An Individualist Review | Ed. Weaver, Asst. Eds. Aldington, H. D., Con. Ed. Marsden | Monthly, 6p |

| Jan – May 1917 | The Egoist | [No subtitle] | Ed. Weaver, Asst. Eds. Aldington, H. D., Con. Ed. Marsden | Monthly, 6p |

| June 1917 – Dec 1918 | The Egoist | [No subtitle] | Ed. Weaver, Asst. Ed. T. S. Eliot, Con. Ed. Marsden | Monthly, 6p |

| Jan – Dec 1919 | The Egoist | [No subtitle] | Ed. Weaver, Asst. Ed. Eliot, Con. Ed. Marsden | Published Irregularly, 9p |

Fig. 1: Various changes to the Marsden Magazines between 1911 and 1919

Given all these changes, it is not easy to sort out the relationships among these three journals. It is apparent, though, that Marsden wished the second to be clearly distinguished from the first. For example, on the back cover of a few early issues of The New Freewoman, at the bottom of a page of quotations praising its p ecessor, this statement appeared:

Some of these expressions of opinion were written to the Editor under the impression that the old paper would be revived. For reasons unnecessary to enlarge upon, that plan has been abandoned in favour of the present plan of commencing an entirely new and separate publication.

On the other hand, for the first three years of The Egoist, the masthead of the third journal carried this statement about its connection to the second: “Formerly the NEW FREEWOMAN.” Thus it is clear that the editor wished to emphasize the break between the first two incarnations of the journal and the connection between the last two. Following this lead, we should be aware that these connections are real. It is easy to assume that the two periodicals with “Freewoman” in the title are quite similar and those with “Freewoman” and “Egoist” are very different, but, in fact, this is not the case.

In what follows here I shall try to sketch the main changes in the Marsden magazines, which evolved as Dora Marsden’s thought evolved, and as various people joined and left its editorial staff, exerting some influence on the contents of the publication. Marsden’s own story has been told well by Les Garner, Bruce Clarke, and Lucy Delap in works mentioned at the end of this document, and much of what I say here is drawn from those books, but this discussion is also based on a close examination of the journals themselves—a process that has been difficult up to now, because it seemed impossible to find full runs of all of them in the same place. With the MJP editions, that difficulty has ended, making possible this version of the history of the Marsden journals. Let us begin, then, with the founding of The Freewoman near the end of 1911. Where did it come from? How did it come about? Why did it happen just then?

It happened when it did because of the timing of Dora Marsden’s break with the Pankhursts’ suffrage organization, the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU). Marsden, who had a degree from the University of Manchester and had been teaching in the north of England, worked for the WSPU for several years and was involved in serious demonstrations that led to her imprisonment for the cause. But she was too independent to accept what she saw as the imperial rule of the Pankhursts—and they were annoyed by her independence, which involved actions unauthorized by the leadership. Marsden was also driven to express her ideas, and was looking for a journal in which to express them. This led to her formal break with the WSPU in 1911 and to her establishment of the magazine she needed. She was joined in this effort by her fellow refugee from the WSPU, Mary Gawthorpe. Both were young women from Yorkshire, with teaching experience and a real desire to change the situation of women in their world. Gawthorpe had become friendly with A. R. Orage when they were both active in the Leeds Art Club, which led to Orage’s journal, The New Age, becoming a model for The Freewoman, and to many of Orage’s contributors writing for Marsden and Gawthorpe’s new journal when it was founded.

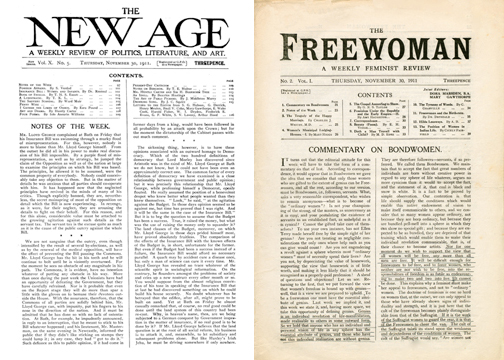

The New Age was a weekly, selling for three pence in November 1911, which opened with a section called “Notes of the Week” on the first page, below the masthead and Contents. The Freewoman also had a masthead and Contents in the same format, sold for three pence, and had a section called “Notes of the Week,” which followed an editorial that began on the first page.

Fig. 2: Cover pages of The New Age (l) and The Freewoman (r) for Thursday, November 30, 1911

Both journals encouraged debates, in which the editors took part, but they also allowed space for views they opposed. Each also published some poetry and fiction, and reviewed plays and art shows. Among the people who appeared in The New Age before writing for The Freewoman are Mary Gawthorpe herself, as well as Teresa Billington-Greig, H. G. Wells, Edward Carpenter, C. Gasquoine Hartley, E. H. Visiak, C. H. Norman, C. J. Whitby, Ashley Dukes, J. M. Kennedy, Edmund B. D’Auvergne, Havelock Ellis, and Huntly Carter. Ezra Pound also wrote for The New Age, but he did not appear in the first Marsden journal. He did enter the scene with The New Freewoman, however, where he was introduced by Rebecca West, who is one of the most important contributors to the first two Marsden journals. West also appeared in The New Age, but she got her start as a regular journalist in The Freewoman, and she played a major role in the changes that occurred in it and its successor.

Like Marsden and Gawthorpe, West was another young woman from the north—having grown up in Edinburgh, though she had been born in London—and she was just nineteen years old when The Freewoman was founded. She had previously been active in the WSPU and became friendly with Mary Gawthorpe, who got her involved in the work of The Freewoman. At that time, West was not Rebecca West but Cicely Fairfield, and her first work in the magazine appeared over that name. After two articles, however, she took the name of Ibsen’s Rebecca West (who has been called “the most demonic heroine in all dramatic literature”), which she kept for the rest of her life. West was writing for other periodicals by then, as well, and one of her reviews brought her in touch with Ford Madox Hueffer (later Ford Madox Ford). Through the gatherings at South Lodge, where Hueffer was living with Violet Hunt, she met other young writers in 1912, including Ezra Pound and Wyndham Lewis. West wrote fiction and literary criticism, as well as journalistic pieces, bringing her literary interests to The Freewoman. It is sometimes assumed that this journal was purely social and political, but that is not the case. It printed poetry and fiction from the beginning. E. H. Visiak, for example, wrote poems for both The New Age and The Freewoman. But the poems were mainly dropped in as filler for short columns; and fiction, when it appeared in The Freewoman, was usually placed near the back of an issue—and was generally quite undistinguished.

Literature was there, however, though the magazine was not founded primarily as a home for literary texts. One of the reasons why Dora Marsden left the WSPU was to find a place where she could express a feminism not entirely confined to the issue of suffrage, which was the only issue welcome in the WSPU’s magazine, Votes for Women. She approached the Women’s Freedom League (WFL), hoping to edit a supplement to their magazine, The Vote, but that did not work out either. What Marsden wanted was to edit a journal that discussed the social and economic condition of women and the whole vexed problem of sexuality, with a critique of conventional sexual morality as leading to the oppression of women. Both suffrage organizations felt that such a discussion would distract from and possibly damage their political cause. But Marsden had come to believe that the only real solution had to go well beyond politics. After months of searching, she found a publisher who would support the sort of journal she hoped to found: Charles Grenville, who owned the radical publishing firm Stephen Swift & Co.

During the months before a publisher was found, Marsden had been bullying (there is no other word for it) her dear friend Mary Gawthorpe into becoming co-editor of the new magazine. Gawthorpe was ill, partly due to the ordeals she endured when imprisoned for the suffrage cause, and she was (quite rightly) afraid that Marsden would attack the WSPU and the Pankhursts. But in the end, after some very bitter letters had been exchanged, she signed on and was listed as co-editor on the masthead when the magazine appeared. Her poor health, however, prevented her from contributing much to the journal, and she finally withdrew officially after a few months. It is very clear, from a study of Dora Marsden’s time with the WSPU and her work in establishing her own journal, that she had a will of steel and could not be intimidated by anyone. Her magazines were hers, and she yielded editorial control only to her trusted friend, Harriet Weaver, who was orderly and reliable, and looked after the parts of the magazine that Marsden did not wish to control. But that was several years after the beginning. The aims of the new journal in its first incarnation were well expressed in a full-column ad that appeared in The New Age on November 23, 1911, the very day when the first issue of The Freewoman was published.

Similar ads appeared in other journals. This one clearly sets the suffrage issue aside, proclaiming an interest in broader issues of concern to women, such as the morality of sex: “An effort will be made to treat the subject of sex morality in a spirit free from bias. Holding the view that conventional sex morality is open to question, the entire subject will be dealt with in an unreservedly fair and straightforward way.” When this actually happened, of course, it provoked outrage, as issues such as prostitution, homosexuality, and “free love” were discussed in open and controversial exchanges among contributors and the writers of letters to the editor. It is also clear that, after a time, Marsden began to find attention focused exclusively on the female side of matters confining. With the thirteenth issue of The Freewoman, “Notes of the Week” turned into “Topics of the Week,” indicating a shift of emphasis from events to ideas. Then, when the second volume of the journal began after twenty-six issues had been published, the subtitle was changed to “A Weekly Humanist Review” to indicate this broadening of Marsden’s interests.

The story of the Marsden journals is, to a very great extent, the story of Dora Marsden’s changing views and interests. Three months into the second volume of The Freewoman, an intellectual event occurred that was to have wide repercussions, giving Marsden’s interests a strong push in a new direction. The editor read a book:

We have just laid aside one of the profoundest of human documents, Max Stirner’s “The Ego and his Own.” A correspondent has asked us to examine Stirner’s doctrine, and shortly we intend to do so. Just now we are more concerned to overcome its penetrative influence on our own minds, by pointing out the abrupt and impossible termination of its thesis rather than to point out its profound truth. (“The Growing Ego,” F 2.38: 221, August 8, 1912)

Marsden’s use of the editorial “we” here leads to her mention of the book’s “penetrative influence on our own minds”—which is perhaps more revealing than it was intended to be. Marsden was, in fact, many-minded. She began by quarrelling with Stirner, but she became more and more persuaded as she continued to examine “his doctrine,” concluding, in an early issue of The New Freewoman, that The Ego and His Own was “the most powerful work that has ever emerged from a single human mind” (NF 1.6: 104). The book was originally published in Germany in 1845, but first translated into English by Steven Byington and published in America in 1907, with the British edition of Byington’s translation not following until 1912—which is when Dora Marsden encountered it. Stirner had been mentioned previously in The Freewoman (January 11, 1912) by Selwyn Weston, but merely as a precursor of Nietzsche. It took some months before Marsden was persuaded to direct her own attention to his book. We may not agree with Marsden’s assessment of Stirner’s work, but we must accept it as true—for her. Her first editorials in The New Freewoman are as Stirneresque as possible, and the magazine’s subtitle, “An Individualist Review,” stems directly from Stirner’s concept of egoism, as does the title of the magazine’s third incarnation: The Egoist. Which means that we need to know something about Stirner to understand the history of these journals, though Stirner’s importance for modernism goes well beyond the Marsden magazines. The combination of Stirner and Nietzsche dominates a certain strain of modernism that connects literary experimentation to the divergent political directions of anarchism and fascism.

This strain of modernism led to books like Vernon Lee’s Gospels of Anarchy and Other Contemporary Studies (1908) and James Huneker’s Egoists: A Book of Supermen (1909), both of which have sections on Stirner and Nietzsche, along with discussions of modern literary figures. It is worth noting that the young T. S. Eliot reviewed Huneker’s book favorably in The Harvard Advocate in October 1909, when he was still an undergraduate. But Dora Marsden was headed in Stirner’s direction before she encountered his work directly. She must have felt that Stirner had given a coherent shape to the very ideas she had been struggling to articulate, that his egoism was the proper mentality for a freewoman, or for any human being. Marsden did not stay there, in the land of Stirner, but she passed through it, as did her journals, so that The New Freewoman, appearing at the height of her interest in Stirner, was more egoistic, even, than The Egoist.

The Freewoman, in addition to causing much outrage, lost some subscribers who did not like the attacks on the WSPU, and it began to lose money steadily, which led to quarrels between Marsden and Charles Grenville, her publisher. The most decisive blow, however, was the refusal of the distributor, W. H. Smith, to continue to display the magazine on newsstands, which deprived the publisher (Stephen Swift & Co.) of even more revenue, at a time when subscribers were shrinking. This situation, combined with Marsden’s own precarious health, led to the closing of the magazine in October 1912, shortly before the completion of its first year. The journal had been fearless—and paid the price. It also brought a measure of fame to Marsden, and created around her a group of loyal followers, who sought to help her re-open the magazine. Some of those followers had been meeting regularly in discussion circles stimulated by the magazine, in which contributors and subscribers met to hear lectures and debate the issues raised in The Freewoman. The most important of these followers were Rebecca West, who had been there since the beginning, and Harriet Weaver, who had been attending the discussion circle and became Marsden’s friend and supporter after their first meeting in February 1913.

West and Weaver played major roles in establishing the second of Marsden’s journals, The New Freewoman. At the beginning, West provided editorial assistance and acted as the London liaison for Marsden, who was living with her family and a friend, Alice Jardine, near Liverpool. Weaver provided financial assistance, starting with a guarantee of £200 to help fund the new journal. Much more than that was needed, and Weaver helped to collect it, finally becoming Treasurer of the magazine when it began in June 1913. The start was not smooth: the Oxford publisher and printer was fired after the first number, and Weaver helped to organize a London company to publish the magazine, The New Freewoman, Ltd., and find a new printer for it as well. The editorials in the first issues were as individualistic and Stirneresque as possible, setting a tone for the new journal that was maintained until the end. But other things happened as well. In the fifth issue, Rebecca West wrote an article on “Imagisme,” which was followed by a group of Imagiste poems by Ezra Pound, and a translation of a work by Remy de Gourmont. This issue marks the beginning of Pound’s influence on the magazine, which was to extend for some years, though his formal connection was very brief indeed.

In the following issue (No. 6: September 1, 1913) Pound reviewed volumes of poetry by D. H. Lawrence, Walter de la Mare, and Robert Frost, and a set of poems titled “The Newer School” appeared, with work by Richard Aldington, H. D., Amy Lowell, Skipwith Cannell, F. S. Flint, and William Carlos Williams. Pound’s review was preceded by the first part of an essay by Ford Madox Hueffer called “The Poet’s Eye,” which was mainly recycled material from the American magazine Poetry, where it had appeared the previous month. Then, in the seventh issue, Pound reviewed two books by John Gould Fletcher, and several poems by Richard Aldington appeared. Fletcher also became a backer of the magazine, providing funds to pay contributors of literary works. Marsden herself approached the question of literature in this issue, by deconstructing the notions of “art” and “taste,” arguing there could be no general standards, only individual judgments of any work of art. This, of course, ran somewhat counter to attempts by the Imagistes to impose their standards on the educated public. At this time, Pound was in fact working both sides of the Atlantic, sending texts, including Hueffer’s essays, to both Poetry and The New Freewoman. Each journal featured Imagisme at this moment, with many of the same poems by Pound and others appearing in both publications, along with the same sorts of explanations and manifestos. Marsden and Harriet Monroe, who edited Poetry, gave Pound space in their magazines, but neither let him dominate.

Domination, however, was what Pound wanted. He got Fletcher to fund the literary section of The New Freewoman for a time, and then he tried to persuade Amy Lowell to fund it. Finally, he got a commitment from John Quinn in New York, but Marsden and Weaver would not sell out. As Pound explained to anybody who would listen, he wanted to control the literary section of a journal, and be able to pay contributors with funds provided by his donor, so he could publish only works that he approved. He finally got much of what he wanted in the spring of 1917, when he joined the staff of The Little Review. At that point he formally severed his connection with Poetry, but he continued to publish in that journal occasionally, and also continued his informal connection to The Egoist. The New Freewoman was a very short-lived journal, running for only thirteen issues, but it marks the turn of Marsden’s magazines toward the aesthetic, with Marsden herself writing on art in the pages of the journal and provoking Pound’s important series “The Serious Artist,” which ran for three issues in 1913 and drew a response from Marsden, “The Art of the Future,” in which she argued with Pound’s ideas while largely endorsing them. When the journal’s name was changed to The Egoist, its interest in literary matters intensified.

The Egoist was the longest-lived of the three journals. This was due to Harriet Weaver’s steady support—both economic and editorial. The magazine’s literary side was underscored by the publication of James Joyce’s novel A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, beginning in the third issue and running through twenty-three more, giving the magazine one of its main claims to literary fame. It was Pound—who had been introduced to Joyce’s work by Yeats—who sent Portrait to Dora Marsden, and Marsden—who accepted it for publication—who is indirectly responsible for Weaver’s becoming Joyce’s patron, which helped support him and his work for the rest of his life. For the first years of The Egoist, Richard Aldington was a very visible literary editor, and he was joined briefly by H. D., with T. S. Eliot taking over for the last year and a half of the journal’s run. As an undergraduate, Eliot had been affiliated with The Harvard Advocate, and he would later found and edit The Criterion. His interest in magazines was a persistent feature of his career, though he never thought of himself as a journalist. His major essay “Tradition and the Individual Talent” appeared in the magazine in two parts in The Egoist’s last two issues. During 1916 and 1917 the journal also serialized Wyndham Lewis’s novel Tarr.

The achievements of The Egoist will be discussed in greater detail in the Introduction to that journal, but we should note here that it shifted from semi-monthly to monthly publication in 1915, while continuing to sell for six pence an issue, with the price rising to nine pence during its final year—1919.

—Robert Scholes, Brown University (2011)

____________________

Endnotes

- See Barbara Green’s “Introduction to The Freewoman” and Susan Solomon’s “Introduction to The New Freewoman and The Egoist.”

Works Consulted

- Clarke, Bruce. Dora Marsden and Early Modernism. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1996.

- Delap, Lucy. The Feminist Avant-Garde. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- Garner, Les. A Brave and Beautiful Spirit: Dora Marsden 1882-1960. Aldershot: Avebury, 1990.

- Glendinning, Victoria. Rebecca West: A Life. New York: Alfred Knopf, 1987.

- Huneker, James. Egoists: A Book of Supermen. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1909.

- Lee, Vernon. Gospels of Anarchy and Other Contemporary Studies. London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1908.

- Lidderdale, Jane and Mary Nicholson. Dear Miss Weaver: Harriet Shaw Weaver 1870-1961. New York: Viking Press, 1970.

- Rabaté, Jean-Michel. “Gender and Modernism: The Freewoman (1911-12), The New Freewoman (1913), and The Egoist (1914-19)” in The Oxford Critical And Cultural History of Modernist Magazines, Vol. 1. Edited by Peter Brooker and Andrew Thacker. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009. 269-89.

- Stirner, Max. The Ego and His Own. Translated by Steven Byington. New York: Benj. R. Tucker, 1907.

- ___. The Ego and His Own. Translated by Steven Byington. Sun City: Western World Press, 1989.