Introduction to Rhythm and The Blue Review

By Carey Snyder

Introduction to Rhythm and The Blue Review

Rhythm (1911-1913) is a self-consciously modernist review of art and literature, based in London and launched by Oxford undergraduates John Middleton Murry and Michael T. H. Sadler in June 1911, with John Duncan Fergusson as art editor. Katherine Mansfield came on board in the fifth issue as assistant editor and core contributor. The idea for the magazine arose during the winter of 1910, when Murry met Fergusson in Paris; Fergusson was a Fauve-inspired Scottish painter, and Murry was taking a break from his studies to see Post-Impressionist art firsthand and to study the French philosopher Henri Bergson in his native context. The title for Rhythm crystallized during their conversations:

One word was recurrent in all our strange discussions—the word “rhythm.” We never made any attempt to define it; . . . All that mattered was that it had some meaning for each of us. Assuredly it was a very potent word. For F—[Fergusson] it was the essential quality in a painting or a sculpture; and since it was at that moment that the Russian Ballet first came to Western Europe for a season at the Châtelet, dancing was obviously linked, by rhythm, with the plastic arts. From that it was but a short step to the position that rhythm was the distinctive element in all the arts, and that the real purpose of “this modern movement”—a phrase frequent on F—’s lips—was to reassert the pre-eminence of rhythm. (Murry 155-56)

For Murry, rhythm is not only “the distinctive element in all the arts,” it is also the defining feature of an artistic personality like Fergusson’s (154). Murry abstracted his idea of rhythm from Bergson’s concept of the élan vital, a “pantheistic life force latent within artistic creativity” (Antliff 82). He elaborated on this idea in his first Rhythm manifesto, “Art and Philosophy,” describing “Modernism”—in what is surely one of the first uses of the term—as that which “penetrates beneath the outward surface of the world, and disengages the rhythms that lie at the heart of things, . . . primitive harmonies of the world that is and lives” (Rhythm 1.1: 12). It was admittedly a vague formula, but therein lurked its strength: as Faith Binckes observes, “rhythm” was a code word for “modernity,” a “flexible signifier of newness” (22). Rhythm was actively engaged in defining, disseminating, and promoting an early version of modernism, one allied with Post-Impressionism and Bergson’s philosophy of creativity.

The magazine trumpeted this cause, declaring that “all who support Modern Art should buy RHYTHM” and “We believe that we have something to say that no other magazine has ever said or had the courage to say” (Rhythm 1.3: “Select Announcements” iv, “What We Have Tried to Do” 36). Part of the self-congratulatory tone stemmed from youthful bravado: as poet and Rhythm contributor Rupert Brooke remarked, “Of course it’s modern. It’s all by people who do good work and are under thirty-five” (qtd. in Hassall 374). Frank Swinnerton, another contributor, recalls that Rhythm was regarded as “youth’s alternative to the far too opulent and well-established English Review of Ford Madox Ford, which had Hardy, James, Conrad, and Wells all writing for it” (Alpers 154). Despite its Oxford associations, Murry conceived of the magazine as anti-academic, as well as youthful: it was “to be kept absolutely cosmopolitan—no suggestions of connexion with Oxford; . . . Oxford is almost the negation of our idea” (April 1911 letter to P. Landon; qtd. in Lea 24).

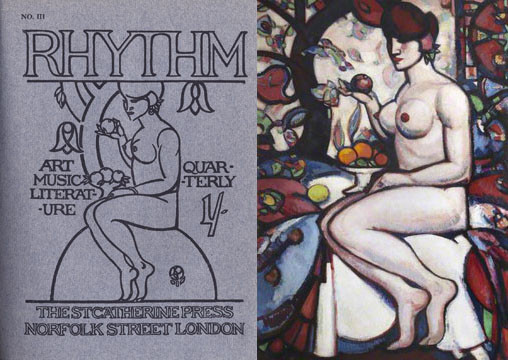

Envisioned by Murry as “the Yellow Book of the modern movement” (157), Rhythm is most notable for its contribution to the visual arts. Providing the core artwork were Fergusson and his circle (more about whom later), while the magazine also featured, for the first time in England, works by such international modernists as Pablo Picasso, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, and André Derain (McGregor 15). Rhythm was printed on fine, heavy paper; its cover—elephantine grey for the first four issues, then Fauvist blue—featured Fergusson’s stylized nude, which served as a prototype for his painting by the same name.1

Figure 1. Left: cover of Rhythm 1.3 (winter 1911). Right: J. D. Fergusson’s “Rhythm” (1911), copyright Perth & Kinross Council. Courtesy of The Fergusson Gallery, Perth & Kinross Council.

Figure 1. Left: cover of Rhythm 1.3 (winter 1911). Right: J. D. Fergusson’s “Rhythm” (1911), copyright Perth & Kinross Council. Courtesy of The Fergusson Gallery, Perth & Kinross Council.

With its reproductions of paintings on glossy insert pages and striking black-and-white line-drawings and woodcuts interspersed through the text, Rhythm was palpably an art object, as well as a forum for publishing and promoting modern art.

On the literary side, the magazine was an important vehicle for Mansfield’s short stories and for manifestos that Murry wrote alone or co-authored with Mansfield. Rhythm was also read for its poetry: it published a group of French poets called the Fantaisistes led by Francis Carco (who is now remembered mostly as a chronicler of French bohemia) as well as the work of the British “Georgian” poets. Georgian poetry is commonly distinguished today from the more experimental modernist literature that would soon be published by Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot, but at the time D. H. Lawrence celebrated it, in his review of the Georgian Poetry anthology, as “a big breath taken when we are waking up after a night of oppressive dreams” (“The Georgian Renaissance,” Rhythm 2.14: Literary Supplement xvii).

Many of the other writers who published in Rhythm are now unfamiliar to us, but rediscovering them recreates a sense of the eclecticism of competing modernisms as they emerged, long before the modernist annus mirabilis of 1922. Among the magazine’s core contributors were Gilbert Cannan, a prolific but now forgotten English novelist whose fiction, essays, and reviews appeared regularly in Rhythm and The Blue Review (which was Rhythm’s short-lived successor: see below), and Wilfrid Wilson Gibson whose poetry was frequently featured in Rhythm, as well as in Edward Marsh’s Georgian anthologies and in Poetry, Coterie, and The New Age. Less frequent contributors to the two journals include Hugh Walpole, a novelist and (like Mansfield) native of New Zealand, who wrote reviews for The Blue Review, and English novelist Frank Swinnerton, author of the 1935 memoir The Georgian Literary Scene, who contributed fiction to Rhythm and reviews to its successor. At the time, Murry considered Rhythm a “success d’estime” and deemed Cannan, Gibson, Walpole, and Swinnerton (along with Lawrence and Brooke) “the most prominent writers of the younger generation” (238).

Publishing History

Rhythm is a classic little magazine: with an average circulation of 250 and a short run of just fourteen issues (June 1911 – March 1913, with a brief afterlife as The Blue Review, May-July 1913), it was continually beset by financial difficulties, changing publishers three times. It began in the summer of 1911 as a quarterly, published by St. Catherine’s Press. After the first four issues, Murry found himself £100 in debt, due to his failure to understand his liability for unsold copies. Fortunately, Mansfield persuaded her publisher, Charles Granville of Stephen Swift and Company, to take on the magazine with its first monthly issue (June 1912). Less than five months later, Granville went bankrupt and fled the country, leaving the editors saddled with £400 further debt, which Mansfield defrayed for a time with her annual allowance of £100, though eventually Murry had to declare bankruptcy. Martin Secker took over the publishing of Rhythm from November 1912 to the end of its run and that of its sequel. Edward Marsh, of Georgian Anthology fame, also reportedly pitched in £100 to help save Rhythm, and consequently was allowed a hand in shaping the magazine’s content in its revived form as The Blue Review (Lea 34).

In February 1913, Mansfield—who had been romantically involved with Murry since 1911—was promoted to associate editor, a role that she maintained in The Blue Review and that signaled her full partnership with Murry in the publications. In retrospect, Murry regarded his and Mansfield’s “desperate and exhausting attempts to keep Rhythm and The Blue Review alive . . . foolish in the extreme” (251); however, these magazines proved a prudent investment in their future by establishing the couple’s credentials in literary London, paving the way for Murry’s prestigious post as editor of the Athenaeum and for Mansfield’s career as a writer. One concrete example of this payoff: just as The Blue Review was folding, Leonard Woolf submitted a story that Murry regretfully returned, along with a note inquiring whether he and “Mrs. Wolff” would care to meet (Alpers 159). That meeting eventually yielded, among other fruit, the publication of Mansfield’s story “Je ne parle pas français” with the Woolfs’ Hogarth Press.

Internationalism

Murry ambitiously planned to have Rhythm distributed “all over the world” and to include manifestations of modernism from around the globe (qtd. in Lea 25). Perhaps unsurprisingly, given its Parisian inspiration, the most emphatic sign of the magazine’s cosmopolitanism was its Francophilia. Rhythm frequently published French poetry and fiction untranslated, along with the regular “Lettre de France” or “Lettre de Paris” feature (also in French), alternately authored by Francis Carco and Tristan Derème, which reported on French periodicals and the French literary scene. Rhythm published and actively promoted what Murry regarded as the quintessentially modernist work of Carco’s school of poetry, the Fantaisistes—including Carco, Derème, Jean Pellerin, and Claudien.2 The magazine also kept readers abreast of art developments in Paris as well as London.

After Mansfield joined the staff, Rhythm’s internationalism became even more pronounced: it could now boast foreign correspondents in four countries (France, Poland, Russia, and America) and distribution agents around the world.3 Among the international contents were Mansfield’s New Zealand stories and her “translations” of the fictitious Russian poet Boris Petrovsky, reviews and illustrations of Les Ballets Russes by Anne Estelle Rice and Georges Banks, Japanese writer Yone Noguchi’s essay on “Hokku” poetry and notes “From a Japanese Ink Slab,” and a retrospective on the Polish painter Stanislaw Wyspianski by Floryan Sobieniowski.

Visual Arts and Dance

The artists in Fergusson’s circle exemplified this cosmopolitanism, exhibiting together in Paris, Cologne, and London. Even before they debuted in the first issue of Rhythm (thus cementing their collective identity as “Rhythmists”), their bold use of color and outline was lauded by New Age critic Huntley Carter in his review of the 1911 Salon des Indépendents (25 May 1911, NA 9.4: 83). While the Rhythmists were known for employing the brilliant color and thick impasto of the Fauves, economic exigency forced them to translate this aesthetic into the boldly contrastive black and white that became part of Rhythm’s visual hallmark. The magazine’s appearance was influenced by its fin-de-siècle predecessors, La Revue Blanche and The Yellow Book, particularly by Aubrey Beardsley’s striking use of line in the latter publication (Scholes and Wulfman, 78-82).4 The Rhythm artists’ collective contributions graphically unified the magazine: they produced not just full-page drawings and paintings but also head and tailpieces (decorative drawings and woodcuts at the beginning and end of articles) and ornate initial letters. They also helped to design and artfully illustrate the advertisements, which first appeared in the third issue. Some head and tailpieces were recycled in multiple issues, which created a sense of visual familiarity in the magazine and helped forge what we might think of as the Rhythm brand.

By reusing certain images and dissolving the boundary between the advertisements and the literary or artistic contents of the magazine, Rhythm also blurred the line dividing avant-garde art and commercial graphic design.5 In an unsigned editorial in the third issue, Murry defends the decision to publish advertising: anticipating the objection that “the admission of advertisements is a degradation of an artistic magazine,” he counters that the editors can’t afford to “bow before the cries of artistic snobbery” and that advertisements will enable Rhythm to continue to say things “that no other magazine has ever said” and to give “the world better drawing than has been seen in one magazine before” (1.3: 36). Even as Murry justifies the magazine’s commercial turn, the ad selections—promoting art dealers like Hanfstaengl, exclusive stores like Heals Furnishings, and galleries like Stafford, where the Rhythmists exhibited—reinforce the impression that Rhythm is a high art magazine.

Despite the perception of little magazines as anti-commercial, Rhythm was not unique in its decision to include advertisements, though having its core artists illustrate them was uncommon. What distinguished Rhythm more from its periodical peers was the unusual number of female artists included. Chief among these was American Anne Estelle Rice, who met Fergusson in 1906 in Paris and began to adopt the vivid colors, formal simplification, and bold outlines of the Fauves. In the magazine’s first number, Michael Sadler lauds Rice’s work as a prime example of Fauvism, admiring Rice’s “rhythmical” use of “strong flowing line” and of “massed colour,” which create a decorative effect (1.1: 17). These attributes are illustrated in the magazine (perforce in black and white) by Rice’s “Schéhérazade” (15), a drawing inspired by the exotic subject matter of the Russian Ballet, like many of Rice’s other figures, both nude and clothed. Through her involvement with Rhythm, Rice developed a close friendship with Mansfield, who dedicated “Ole Underwood” to the painter (Rhythm 2.12: 334). Rice later reciprocated by painting Mansfield’s portrait.

Two other important female Rhythmists were the English Jessica (Jessie) Dismorr and the American Marguerite (Margaret) Thompson, who shared studio space and studied together at the Académie de la Palette in Paris in 1911. Dismorr had studied at London’s Slade School in 1902 and 1903; the wealthy and well-connected Thompson had dropped out of Stanford University to come to Paris, and met Fergusson at Gertrude Stein’s salon. Both women began exploring “the fluid contours and brilliant colours which became the hallmarks of the ‘Rhythmists’” (Binckes 136). Dismorr exhibited with the group at Stafford in 1912 and contributed numerous drawings to Rhythm, including one of modern dancer Isadora Duncan (1.2: 20). Like Rice, Dismorr was a prolific painter and illustrator of the female nude—which was “exceptionally unusual, if not unique” in periodicals of the period (Binckes 158).6 In 1913, an encounter with Wyndham Lewis led to a dramatic change in Dismorr’s style, ultimately converting her into a Vorticist. She was one of two women to sign the movement’s manifesto, became a member of the Rebel Art Centre, exhibited with the Vorticists, and contributed a number of paintings, poetry, and prose pieces to Blast (1914), which some have argued is a successor to Rhythm.7

Margaret Thompson/Thomson (both spellings are used in Rhythm) went on a world tour from October 1911 to April 1912, visiting Egypt, Palestine, India, and the Far East; several of her pen-and-ink drawings of these destinations appear in Rhythm in 1912 (see, for instance, 2.5: 5 & 13). They combine crude perspective and composition with rustic scenes, contributing to the magazine’s marked strain of exoticism. Her drawings and linoleum cuts are interspersed throughout the magazine’s run.

Also appearing throughout the magazine are Dorothy “Georges” Banks’ illustrations and caricatures (including one of Mansfield: 2.9: 193). Banks’ inclusion at the Stafford show represented a significant step in elevating the trivialized genre of caricature. As Rhythm’s Paris Theater Correspondent (with Rice), Banks illustrated and reported on Diaghilev’s Petrouchka (2.6: 57-63) and reviewed Leon Bakst’s production of Oscar Wilde’s Salome (2.8: 169-73), among other performances.

Male Rhythmists of note include Samuel John (S. J.) Peploe and Othon Friesz. Like Fergusson, Peploe is considered a Scottish colourist; hailing from Edinburgh, he moved to Paris in 1910 and fell under the influence of the Post-Impressionists. Peploe’s small sketches and woodcuts are threaded through Rhythm, along with a smattering of larger drawings. Friesz was a native of Le Havre, France, who exhibited with the Fauves in 1906. In Rhythm, three of his landscapes and two of his nudes are featured. Fergusson’s many connections in Paris meant that Rhythm was also able to publish several works by Picasso, and one work each by Paul Cézanne, Henri Rousseau, and Fauvist André Derain. Murry and Mansfield befriended the artist Henri Gaudier (who took his partner Sophie Brzeska’s name), which led to his work being featured as well, until the two couples had a bitter falling out and Gaudier-Brzeska broke with the magazine. Gaudier-Brzeska developed a close friendship with Pound and, like Dismorr, became a Vorticist and contributor to Blast.

When he signed on as art editor, Fergusson declared that he wanted a “cheap, not a de luxe magazine,” from which “any herd boy [could obtain] the latest information about modern painting from Paris” (Morris 64). At one shilling per issue, Rhythm was affordable, though the editorial assumption that its readers were conversant in French as well as English probably strained the “herd boy” ideal. The magazine not only disseminated avant-garde art as a circulating gallery space, it also provided commentary and exegesis on modern artworks and movements. Instrumental in providing this critical context was cofounder Michael T. H. Sadler, who later changed his name to “Sadleir” to avoid confusion with his father—art collector, Vice-Chancellor of Leeds, and patron of Rhythm. Sadler (I preserve the original spelling) later became famous as a novelist, publisher, and book collector.

Sadler’s criticism was especially important in positioning Rhythm within debates about modern art. In deeming Rice a Fauvist in the first issue, Sadler side-stepped the label of “Post-Impressionism” associated with Roger Fry’s influential exhibition at Grafton Gallery, which had at once shocked the general public and thrilled the avant-garde by violating aesthetic expectations.8 Sadler thus strategically bypassed Bloomsbury, deeming Fry’s term for the movement “futile and misleading” (1.1: 14) and returning to the French nom d’école to which Fergusson, Rice, and Peploe all had a claim. Murry, too, sought to disentangle Post-Impressionism from its Bloomsbury associations. Indeed, recent scholars have viewed Rhythm as a “dissenting formation” against the “hegemonic Englishness of Bloomsbury” (Brooker 336).9

Other modern artists that Sadler discussed include Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, André Derain, and Wassily Kandinsky. An early enthusiast of Kandinsky’s work, Sadler purchased some of his woodcuts and in 1914 translated his Über das Geistige in der Kunst as The Art of Spiritual Harmony. Readers in London and beyond were first exposed to Kandinsky’s art theories in Sadler’s essay “After Gauguin” (Rhythm 1.4: 23-29). Apparently feeling that three was a crowd on the masthead, Sadler withdrew after Mansfield joined the staff in June 1912, but he returned as a contributor in the last two issues and in the first number of The Blue Review (Lea 32).

Rhythm displayed a broad-based commitment to the arts that extended beyond the visual, as reflected in the magazine’s subtitle, “Art Music Literature.” Although the treatment of music itself was nominal, the rhythm motif adapted a musical metaphor to various modes of creative expression. The Ballets Russes epitomized and helped inspire the cross-fertilization of the arts that Rhythm celebrated: along with paying tribute to the ballet by illustrating and reporting on these performances, the Rhythmists owed their style in part to the decorative aesthetic of Leon Bakst’s sets and costumes. Modern dance forms another motif in the magazine’s pages—evident, for example, in Carco’s “Les Huit Danseuses” (1.1: 21), Dismorr’s drawing of Isadora Duncan (1.2: 20), and an advertisement for Émile Jaques-Dalcroze’s book The Eurhythmics of Jaques-Dalcroze (2.11: xvi).

Fergusson gave up his post as art editor in November 1912, at which time the magazine became less avant-garde, as Peter Brooker has argued (385). In the last few issues, Rhythm is less visually interesting, and even resorted to recycling Rice’s images. In The Blue Review, art critic O. Raymond Drey expresses significant reservations about Picasso’s Cubism and the Futurism of Gino Severini, further distancing the sequel from its avant-garde predecessor.

Primitivism

Both the magazine’s Fauvist roots and its fixation on the Ballets Russes formed part of a larger fascination with the primitive and exotic that runs through Rhythm’s pages, constituting a familiar strain of modernism. In the first number’s opening essay, Frederick Goodyear lauds a new class of “neo-barbarian” artists who succumb to the “call of the wild” (“The New Thelema,” 1.1: 3)—a sentiment that Murry echoes in his manifesto by calling for modern art to be unfettered and primal (“Art and Philosophy,” 1:1: 12). This motif is reinforced by the artwork in the issue, including Rice’s “Schéhérazade” (15) and Thompson’s linocut of a tiger stalking a monkey (12), which serves as a tailpiece for Murry’s manifesto and is reused later in association with Mansfield’s writing. (It is this image which prompted Gilbert Cannan to dub Murry and Mansfield “the two tigers.”) Thompson’s aforementioned images of India, Egypt, and Palestine and Sadler’s celebration of Gauguin’s “wild, idyllic life” (1.3: 31) reinforce the magazine’s pervasive exoticism.

Mansfield’s literary contributions work both within and against the romantic primitivism and exoticism that pervaded Rhythm’s pages. Murry praised Mansfield’s “The Woman at the Store” (1.4: 7-21)—her debut story in the magazine about murder and degeneration in the New Zealand backwoods—as realizing what had previously been only a “vague idea of what an appropriate story for Rhythm should be”; for him, the tale also gave proof to the slogan, “Before art can be human again, it must learn to be brutal” (Murry 184).10 Mansfield contributed two more stories, “Ole Underwood” and “Millie,” in which New Zealand emerges as a rough and alien country, fodder for a new and “brutal” art (Rhythm 2.12: 334-37 and Blue Review 1.2: 82-87). Together with Mansfield’s “Sunday Lunch,” a satire of literary Bohemia signed by “The Tiger” (Rhythm 2.9: 223-25), this body of work may be seen as undercutting metropolitan exoticism. On the other hand, her story “How Pearl Button Was Kidnapped” (2.8: 136-39), published under another pseudonym, Lili Heron, idealizes Maori people in the vein of Gauguin’s Tahiti-inspired art.

Rivalry with The New Age

Mansfield’s involvement with Rhythm extended beyond her literary and editorial contributions; she was also an important catalyst for the magazine’s fierce rivalry with The New Age, a socialist weekly published in London that is recognized today for its role in stimulating and disseminating early modernism. Mansfield got her start in The New Age, publishing many stories that would form her first collection, In a German Pension (1911), and sharpening her satirical pen in short sketches and parodies, some co-written with Beatrice Hastings, a core contributor who was also the journal’s unsung assistant editor and romantic companion of A. R. Orage, the journal’s editor.11 From February 1910 to March 1912, Mansfield formed part of the magazine’s inner circle, even sharing lodgings with Orage and Hastings for several months. The relationship began to sour when The New Age ran an unfavorably review of In a German Pension (21 December 1911, NA 10.8: 188), which prompted Mansfield to seek other venues for publication and ultimately leave The New Age to join Rhythm’s staff. Seeing her departure as an act of betrayal, Orage and Hastings retaliated in a string of attacks on Rhythm and on Mansfield’s writing and character.12 Under the pseudonym R. H. Congreve, Orage satirized his former protégé in a six-week series in The New Age (“A Fourth Tale for Men Only,” May 2 – June 6, 1912), and Hastings, using the pseudonym Alice Morning, attacked Mansfield as a “changeling” who is both amorously and professionally promiscuous (“The Changeling,” 2 January 1913, NA 12.9: 212).

The rivalry between the two journals was clearly personal, but it was also professional, as each publication competed for a niche within the same “periodical community”—which Lucy Delap describes as a group of journals that “promote debate and controversy between each other, exchange material, share contributors, and generally inhabit the same intellectual milieu” (388 n48). The New Age covered not only politics but also arts and letters. Though it presented commentary on Post-Impressionism two months before Fry’s exhibition, visual art itself was scant in the magazine’s pages until the inception of Rhythm, and its expansion was possibly inspired by the smaller magazine’s example (Scholes and Wulfman, 88-94). As the first British journal to publish the work of Picasso and Gaudier-Brzeska, Rhythm challenged The New Age’s claim that it defined the “new” for English audiences; it also recruited several contributors from The New Age, including, with Mansfield, W. L. George, Frank Harris, and Holbrook Jackson. The New Age renewed its criticism of Rhythm when the latter published an André de Segonzac sketch called “Les Boxeurs” in the Spring 1912 issue; a painting by Segonzac with the same name had been reproduced in The New Age two months earlier, and the weekly wasted no time in pronouncing Rhythm derivative.13 Murry defended Rhythm from this charge in a letter to the New Age editor (4 April 1912, NA 10.23: 551) and, in a more general way, he justified the magazine’s existence in a series of Rhythm manifestos, some co-written with Mansfield, the polemical tone of which may thus be seen as a product of periodical turf warfare.

The Blue Review

After perusing Rhythm, one is struck, when turning to its three-issue successor, The Blue Review (May- July 1913), by the absence of stunning visuals that made Rhythm so distinctive. In place of the stylized nude featured on the cover of Rhythm, the front of The Blue Review is conspicuously bare, with only the table of contents displayed—and, apparently due to a printing error, only a blank box for the second issue. The magazine’s stark cover is matched by its unadorned interior: gone are the head and tailpieces, the illustrated ads, and ornate initial letters. The minimal artwork that is included—five images in the May issue, four in June, and just one in July—is not particularly striking, and these images are mostly sequestered in the middle of the magazine. Without Fergusson at the helm and the Rhythmists on board, The Blue Review does nothing significant with the visual arts, although it still declares its investment in the subject with a regular feature called “The Galleries,” penned by Sadler, Edward Marsh, and O. Raymond Drey. With sections on Music (underrepresented in Rhythm), Theater, Literature, and Painting, The Blue Review remains faithful to its predecessor’s broad-based commitment to the arts. It is less international, however, dominated by British poets and painters, although it extends Rhythm’s Francophilia and makes a few other gestures toward the cosmopolitan outlook of its predecessor.

Along with contributions by Mansfield and D. H. Lawrence, who published an essay on Thomas Mann and the short story “The Soiled Rose,” The Blue Review was dominated by the work of the Georgian poets, who “flooded in in the wake of Edward Marsh” (Lea 34). Lawrence celebrated these poets in Rhythm, which in turn promoted Marsh’s anthology—including works by Brooke, W. W. Gibson, Lascelles Abercrombie, and W. H. Davies, all of whom found their way into The Blue Review. Though critics have followed Murry’s representation of these two magazines as virtually interchangeable, Peter Brooker has argued that this view “simply will not stand up to scrutiny”: Rhythm, at least until Fergusson’s departure in December 1912, “was the more inventive and radical . . . and belonged to a more avant-gardist and international, or at least Anglo-European formation than The Blue Review” and Murry’s later magazines (324). However, Faith Binckes has challenged this reading of The Blue Review as a pale sequel to Rhythm, dominated by the overly tame Georgians; she reads the later magazine as being “more adversarial” than it is traditionally seen, arguing that “in 1913 there was every reason for the contributors of the Blue Review and the Georgian anthology to imagine that they would be the ones doing the defining” of modernism (168).

Rhythm and The Blue Review are a good place to start to rediscover some of the players who contended for a place in the emerging field of modernism. When Roger Fry decided to exclude Rhythmists like Fergusson, Rice, and Peploe entirely from the Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition in 1912, the group staged a rival exhibition at the Stafford Gallery. One critic commented, “It is difficult to understand why no place should have been found in Grafton-street for their interesting work. . . . All these artists express modernity; each of them belongs to to-day” (Robins 108). The remark sums up the best reason for rediscovering the artists and writers associated with Rhythm: many of these figures have been forgotten by literary and art history, but they belong in our discussions of the period to the extent that they, too, “express modernity.”

—Carey Snyder, Ohio University

____________________

Endnotes

- See Antliff 83 and Binckes 148-50. The MJP would like to thank the Perth & Kinross Council for allowing us to reproduce Fergusson’s “Rhythm” (1911) in this article. Readers interested in seeing more images of Fergusson’s work should visit the websites at The Fergusson Gallery and The University of Stirling Art Collection.

- In the April 1911 letter to P. Landon already cited, Murry wrote, “Modernism means, when I use it, Bergsonism in Philosophy. . . . Now Bergsonism stands for Post Impressionism in its essential meaning—and not in the sense of the Grafton Exhibition. . . . It stands equally for Debussy and Maehler in music; for Fantaisisme in Modern French literature” (qtd. in Lea 24).

- In the August 1912 issue, a list of “Agents for Rhythm Abroad” identifies six booksellers in Paris and one each in New York, Munich, Berlin, Helsingfors [Helsinki], Warsaw, and Krakow (2.7: 124).

- For more detailed discussion of visual art in Rhythm, see Binckes, McGregor, and Antliff.

- See Binckes 133-55. Scholes and Wulfman similarly note, concerning Rice’s drawings of the Russian Ballet, that “their technical links to the more overt ads are readily visible” (116).

- See, for example, Dismorr’s illustrations for Jean Pellerin’s poem “Le Petit Comptable” (Rhythm 1.4: 31) and for Tristan Derème’s second “Petit Poème” (1.3: 18). For a discussion of the gender politics of these artists’ treatment of nudes, see Brooker 332-33 and Binckes 158-63.

- See Maryssa Demoor, Scholes and Wulfman.

- See Robins for further discussion of public reactions to post-impressionist art in Britain.

- See also Scholes and Wulfman, and Binckes 132-40. Murry specified that the Post-Impressionism he associates with modernism is not that associated with the Grafton Exhibition (Murry 24).

- The slogan is adapted from a quotation from Poems and Translations (1911) by the Irish playwright J. M. Synge; Murry substitutes “art” for “verse” (Scholes and Wulfman 74).

- For more on Hastings’ contributions to The New Age, see Ardis and Snyder.

- The March 28, 1912 issue lashes out at Rhythm, claiming that there is “no single page that is not stupid, or crazed, or vulgar—and most are all three,” and faults Mansfield’s “The Woman at the Store” for “plough[ing] the realistic sand, with no single relief of wisdom or of wit” (10.22: 519). Other New Age attacks on Rhythm occur, in 1912, in the April 4 (10.23: 548), April 18 (10.25: 589), July 18 (11.12: 282), and August 15 (11.16: 377) issues.

- The Segonzac painting appeared in the Art Supplement to The New Age for January 18, 1912 (10.12: Art Supplement); the March 28 issue contained the accusation that Rhythm lacked originality (10.22: 519).

Works Cited

- Alpers, Anthony. The Life of Katherine Mansfield. New York: Viking, 1980.

- Antliff, Mark. Inventing Bergson: Cultural Politics and the Parisian Avant-Garde. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1993.

- Ardis, Ann. “The Dialogics of Modernism(s) in The New Age.” Modernism/modernity 14.3 (September 2007): 407-34.

- Binckes, Faith. Modernism, Magazines, and the British Avant-Garde: Reading Rhythm, 1910-1914. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2010.

- Brooker, Peter. “Harmony, Discord, and Difference: Rhythm (1911-13), The Blue Review (1913), and The Signature (1915).” The Oxford Critical and Cultural History of Modernist Magazines. Volume 1. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2009. 314-36.

- Cumming, Elisabeth. Introduction. Colour, Rhythm & Dance: Paintings & Drawings by J. D. Fergusson and His Circle in Paris. Edinburgh: Scottish Arts Counsel, 1985.

- Delap, Lucy. “Feminist and Anti-Feminist Encounters in Edwardian Britain.” Historical Research 78.201 (August 2005): 377-99.

- Demoor, Marysa. “John Middleton Murry’s Editorial Apprenticeships: Getting Modernist ‘Rhythm’ into the Athenaeum, 1919-1921.” English Literature in Transition 52.2 (2009): 123-43.

- Hankin, C. A., ed. The Letters of John Middleton Murry to Katherine Mansfield. London: Constable 1983.

- Hassall, Christopher. Rupert Brooke: A Biography. London: Faber and Faber, 1964.

- Lea, F. A. The Life of John Middleton Murry. London: Methuen, 1959.

- McDonnell, Jenny. Katherine Mansfield and the Modernist Marketplace: At the Mercy of the Public. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

- McGregor, Sheila. “J. D. Fergusson and the Periodical ‘Rhythm.’” Colour, Rhythm & Dance: Paintings & Drawings of J. D. Fergusson and his Circle in Paris. Elisabeth Cumming, ed. Edinburgh: Scottish Arts Counsel, 1985. 13-17.

- Morris, Margaret. The Art of J. D. Fergusson: A Biased Biography. Glasgow: Blackie, 1974.

- Murry, John Middleton. The Autobiography of John Middleton Murry: Between Two Worlds. New York: J. Messner, 1936.

- Robins, Anna Gruetzner. Modern Art in Britain: 1910-1914. London: Merrell Holberton, 1997.

- Scholes, Robert and Clifford Wulfman. Modernism in the Magazines. New Haven: Yale UP, 2009.

- Smith, Angela. Katherine Mansfield: A Literary Life. Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2000.

- Snyder, Carey. “Katherine Mansfield and the New Age School of Satire.” Journal of Modern Periodical Studies 1:2 (2010): 125-58.